Analysis of a Comparison of Formal Methods for Evaluating the Language of Preference in Engineering Design

I. Summary of Research

Introduction and Background

In Dong and Ji’s work on engineering design language, linguistic data is considered from the perspective of design improvement [8]. Dong and Ji seek to understand preferences based on the nuanced language of the designer. Using utility theory as applied to Decision-Based Design methods, Dong and Ji attempted to reduce inconsistencies.

The first method discussed by Dong and Ji for reducing inconsistencies was to reduce the cognitive burden on designers by using Appraisal Preference Analysis. This allowed the authors to model language and attitudes mathematically. This system allows for reducing bias in the preference of a given option when presented to a decision-maker.

The second method discussed by Dong and Ji is called Preferential Probabilities from Transcripts. This uses probability modeling to attempt to determine preference information based on word density in conversation. Transcripts from meetings are analyzed for word content. Heuristics are applied to determine the overall viewpoint of the team with regard to the project options [1]. This can be compared to surveys to validate results.

Within the confines of linguistic theory, there are several ways to evaluate statements. Declarative statements that do not convey information about the product are difficult to score in terms of preference. However, polarizing comments declaring that objective features of a product are undesirable can be easily scored. If a comment is said in such a way as to cede responsibility for the opinion through use of qualifier words such as “maybe,” “seems to,” or “in my opinion” then the comment may be considered to be less sincere and can be scored accordingly [1].

Methods

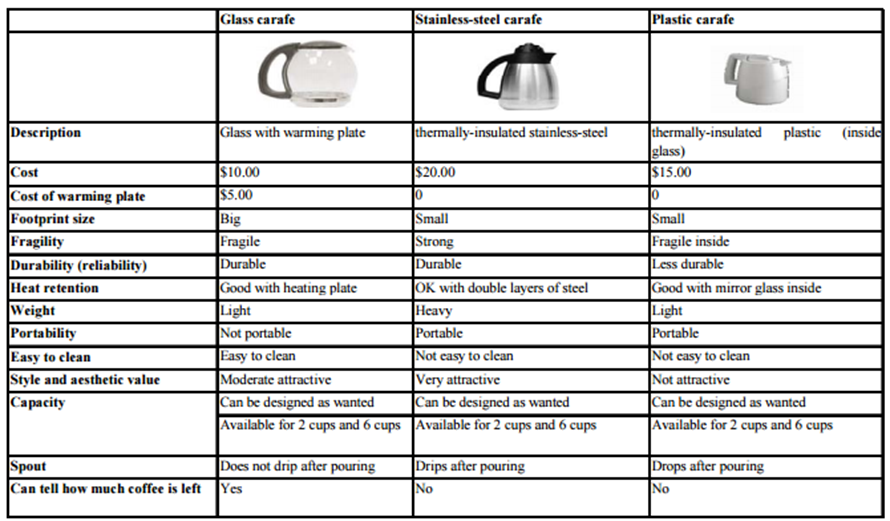

To create a conversation that could be analyzed using linguistic heuristics, Dong and Ji created a case study for design alternatives involving a coffee carafe. As shown in Table 5, three options were provided for discussion among a small group of three people. The individuals were given a budget of 35$ and told to discuss the products.

The conversations regarding the products were periodically paused to conduct surveys on the products. To promote conversation, full knowledge of one product was provided to one member of the group while only partial knowledge of the other two products would be held by that member. As a result, each team member was forced to discuss options with the other team members to uncover the full specifications of all products [1].

Results

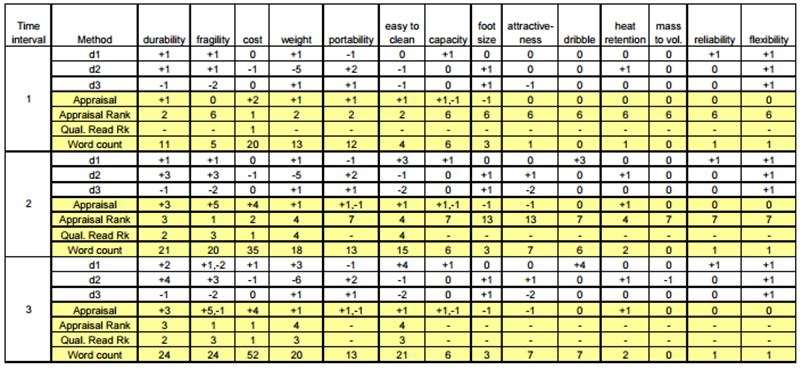

Once the time for the study had elapsed, the results were tabulated. Table 6 summarizes the results. The conversation was scored using Dong and Ji’s heuristics [8]. This allowed for the appraisal calculations to be compared against survey results.

By comparing the heuristic results with survey results, Dong and Ji discovered that both sets of preferences tended to be equivalent. In general, language was found to be a reliable determiner of what the survey results would find. Thus, the idea of appraisal linguistics studies was validated for this case study.

II. Discussion of the Paper

Dong and Ji have made a compelling case for linguistic study. Although the implication that conversation will reveal design bias may seem to be common sense, the authors have quantified this concept mathematically. Because of this quantification, Utility Theory-based design methodology y may see an additional tool available for use. As linguistic studies may allow for uncovering systemic biasing from designers, decision-makers will be better equipped to critically view recommendations in the future. However, there is still much work to be done in this field.

In this paper, the authors validate their findings through the use of a case study. However, the case study used involved three individuals with no repetition. Additionally, there was training provided to the group which may have skewed results. The lack of repetition combined with no control group and an extremely small sample size causes this study’s findings to be inadmissible for proving the validity of linguistic heuristics in design. As a result, the only conclusion that can be drawn from the case study is that further research is necessary to draw any definitive conclusion regarding the validity of linguistic heuristics in design.

III. Future Possibilities

Based on this article, future designers may be able to monitor their design reviews for bias regularly. Linguistic studies, despite the risk of privacy invasion, allow for unparalleled discovery of preference before the designer is aware that it exists. As discussed by Dong and Ji, computational linguistics currently involves the use of consumer-generated information available on the Internet.

By culling social media, modern “Big Data” corporations determine trends to allow for ideal market positioning. Similarly, it may be possible to use computational linguistics to monitor the communications that designers have regarding projects both in-person and remotely over telecommunications and email/instant messenger services. Despite the potential advantages, the privacy concerns of such an activity are substantial.

[1] Honda, T., Yang, M. C., Dong, A., and Ji, H., 2010, “A comparison of formal methods for evaluating the language of preference in engineering design,” Proc. 2010 ASME IDETC Int. Des. Eng. Tech. Conf. Inf. Eng. Conf. IDETC/CIE2010, 5, pp. 297–306.

Member discussion